The Exmouth

Apart from the The Girona, the waters of the North Antrim coast were the scene of another maritime disaster with great loss of life.

In 1847, During the Great Hunger, the Brig Exmouth left Derry (Londonderry) for Quebec. Rather than sailing west across the Atlantic, a gale blew her east and she was wrecked on the island of Islay, off the coast of Scotland. There were only three survivors.

She was registered for 165½ passengers (two children count for one adult). Nevertheless there were 240 passengers and a crew of 11. Initial reports gave the official number: 165. The passengers were, mainly, small farmers and tradesmen with their families. There were may women with their children (there were just 60 male passengers) who were to join their husbands who emigrated earlier and had established homes for their families. Of the 108 bodies recovered, 63 were children (less than 14 years of age) and 9 infants.

The information we have is, principally, from the three survivors. Their stories were printed in several newspapers and copied to others. Links to these are found below. This disaster is well commemorated on the web, in sites interested in history, tourism, genealogy and heritage; again there are links below. Most of these websites reproduce a newspaper account verbatim. The story speaks for itself.

The ship was a passenger one that sailed from Londonderry to Quebec on April 25, 1847. Aboard where 11 crewmen, 244 Irish immigrants. The ship was only registered for 165 passengers, but a large number of the passengers were children and two children were counted as one adult passenger hence the 244.

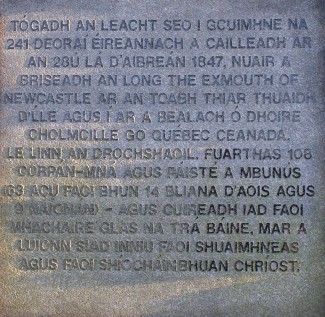

The loss of the emigrant ship Exmouth Castle on April 28 1847, is one of the most tragic peacetime incidents of all Northern Ireland shipwrecks. The vessel was owned by Mr. John Eden of South Shields. It departed from Londonderry bound for Quebec on Sunday, April 25, with two hundred and forty emigrants plus three women passengers and eleven crew aboard. A memorial was erected near Sanaigmore Bay on Isaly to remind of this terrible tragedy. The Gaelic and English Text is as follows:

This memorial is dedicated to the memory of 241 Irish emigrants who lost their lives on April 28, 1847, when the brig ‘The Exmouth of Newcastle’ out of Derry and bound for Quebec, Canada, at the time of the great famine, was wrecked on the N/W coast of Islay. 108 bodies, mostly women and children (63 under the age of 14 and 9 infants), were recovered and are buried under the soft green turf of Traigh Bhan. May their souls rest forever in the Peace of Christ.

Gaelic Text on the monument: Tógadh a leach seo I cuisine na 241 deoraí éireannach a called ar a 28ú lá d’aibreán 1847, nuair a breadth along the Exmouth of Newcastle ar a touch thiar thuaidh de agus í ar a bealach ó choice cholmcille go québec Canada, le linn a drochshaoil, furthers 108 corrán-mná agus fáisté a bonus (63 acu faoi bhun 14 bliana does agus 9 Tioman) – agus cuireadh iad for machine glas na trá báine, mar a lion salad inniu faoi shuaimhneas agus faoi shiochain Bhutan christ.

The following is an edited account from the Illustrated London News of May 8, 1847:

We are sorry to have to record the loss of the ship Exmouth under harrowing circumstances, the loss of life being very significant. According to the statement of three sailors, the sole survivors of the wreck, who arrived in Glasgow on Saturday evening, the Exmouth sailed from Londonderry for Quebec with a light southwest breeze. She had a crew of 11 men (including Captain Isaac Booth) and about 240 emigrants, principally of small farmers and tradesmen with their families. Many were females and children going out to join their fathers and protectors, who had already settled in Canada. There were also three cabin passengers, young unmarried ladies of the middle classes and two sisters, on their way to join their relatives at St. John, New Brunswick.

The vessel was registered for 165 passengers, but, as two children count as one adult, and as a substantial proportion were under age-there being only about 60 men amongst the passengers – the survivors of the wreck think that the total number of these ill-fated emigrants must have amounted to 240. The ship lost sight of land at about four o’clock on Sunday afternoon. The morning breeze, which had been light, increased to a gale during the day. At about eleven p.m., it came in terrific squalls, accompanied by heavy torrents of rain. They then furled the fore and main sails. The wind, which had been to the westward at first, veered northerly, and the storm increased in violence, which blew the two topsails from the bolt-ropes. The crew then commenced to bend other topsails, which they furled, but at about three in the morning, they were blown from the gaskets. The ship was now driving to the southward and eastward. The reason the master did not stand to the westward, where he would have ample sea room, was for the purpose of attaining some harbour of refuge, where he might repair damages and replace the sails.

On Monday forenoon, the long boat was unslipped by the force of the seas, which broke over the vessel, and in the course of the same forenoon, the bulwarks were stove in, and the lifeboat washed away. The gale continued with the same violence during the whole of Monday night and Tuesday. About eleven o’clock on Tuesday night (April 27), land and light were seen on the starboard quarter, which Captain Booth, at first, took to be light on the Island of Tory, off the northwest coast of Ireland and, in the belief that he thus had ample sea-room in the course he was steering, he bore along. As he drifted near the land, however, and observed that the light was flashing instead of a stationary one, he became conscious of his error and dangerous position and made every effort to repair it by bringing the ship farther northward and westward and, with the view of ‘clawing’ her off the land, the main topsail and the foretopmast staysail were set, and the jib half hoisted.

The effort, however, could have been more effective; the ship soon got amongst the broken water and, at half-past twelve on Wednesday morning, was dashed amongst the rocks. If the above be a correct version of the impression on the captain’s mind as to his position, it is distinctly spoken to by two of the survivors – the result shows that he must have been fully a hundred miles out of his reckoning. Still, it could not reasonably be otherwise. The sun was obscured all the time by black clouds; the moon was only seen through a heavy haze at intervals, and from these causes, it was impossible that any observation could be taken. The light seen was, in reality, that of Oransa or Oversay, on the point of the Rhinns or Runs of Islay, to the northwest of the entrance of Lochindaal; and the land seen, and on which the brig eventually struck, was the western part of the iron-bound coast of the island.

She went ashore and, after striking once, was dashed broadside on alongside the rocks, which rose to the height of the masthead. She struck violently against the rocks three times, and at the fourth stroke, the mainmast went by the board and fell into a chasm of the stone. The fourth collision with the rocks broke the main into splinters. This recoiling wave had dragged the ship and the mast fragments, which adhered to her by the rigging, further into the sea and thus cut off from the dense mass of human beings on board every chance of escape. Had the wreck remained in the chasm where it was initially thrown and from which the three survivors escaped, it might have been used as a bridge by the others, but unhappily, this last possibility of relief was taken away. There was no cry from the multitude cooped up within the hull of the ill-fated brig, or at least it was unheard, for the commotion of the elements was so furious that the men on the top could scarcely hear each other at the top of their voices.

The emigrants, therefore, must have perished in their berths as the rocks rapidly thumped the bottom out of the vessel. The three men who had escaped to the rock, so soon as the ship entirely disappeared, searched anxiously for some outlet by which they might reach the mainland. Still, none such could be found, and they finally took shelter in a crevice, which, however, did not shield them from the rain, which fell heavily all night, and here remained till grey daylight. They then discovered an opening, through which they scrambled to the summit. After the day had fairly broken, they observed a farmhouse about half a mile distant. Thither they proceeded and were most hospitably nourished and put to bed. They were thoroughly worn out by exhaustion, not one of the crew having been in bed from the moment the ship left Derry. They were at the same time nearly naked, from having divested themselves of their heavy clothing when the Exmouth struck and lost part of that which remained when scrambling on the rigging and amongst the rocks.

The hospitable farmer and others apprised by him went to the scene of the catastrophe, but of course, too late to help and only to gaze on the desolation. Mr. Chiene, Islay’s factor, soon heard of the event and kindly furnished the men with a passage to Glasgow. At the latest date of our advices from Islay, about 20 of the bodies had come ashore. They were principally females, with one little boy amongst them, and as many of them were in their night clothes, the probability is that they were those who had rushed upon deck at the first alarm caused by the striking of the ship.

108 bodies were found ashore on the island of Islay and were buried in a common tomb in Tràigh Bhàn, where a memorial also stands.

Accounts of this shipwreck elsewhere on the web

Newspaper Reports of the Exmouth Shipwreck

Several reports are available on the IED (Irish Emigration Database):

Reports on other sites:

- An Australian Maritime History site has the news report from the Times (Australian) which was reprinted from the Scots Reformers Gazette

- The Mind of James Donahue has the Illustrated London News account

- A tourist site, the Causeway Costal Route has the report from the Glasgow Morning Star

Memorial

- There is a memorial to those lost from the Exmouth in the Maritime Memorials site;

- A song about the tragedy, written by William Roche, one of the survivours is available at: Tobar an Dualchais (the well of heritage)